The History of Staircase Construction

JOIN US ON A JOURNEY THROUGH THE ART OF STAIRCASE CRAFTSMANSHIP

Staircases are among the oldest architectural elements in history. Pinpointing their exact origins, however, proves challenging. It is widely accepted that humans were using steps to overcome elevation differences thousands of years before Christ. We have selected some significant historical examples for you.

Fig. 1: The earliest known decorative use of staircases can be traced back to Göbekli Tepe (Turkey, likely 10th millennium BC).

Fig. 2: The Ziggurat of the Moon God Nanna in Iraq, a stepped temple over 4,000 years old.

Fig. 3: The Kukulcán Pyramid in the Mayan ruins of Chichén Itzá (around the 11th/12th century).

Staircase construction and design have evolved countless times over the centuries, reflecting the spirit and symbolism of each architectural era. Throughout history, master builders with exceptional talent and creativity have crafted unique staircases that transcend time. The markiewicz team is proud to be part of this select group of artisans shaping sophisticated staircase design today

STAIRCASES AS ARCHITECTURAL MASTERPIECES

Among all architectural elements, staircases hold a unique position. They not only shape a building’s character but can even outshine it entirely. Perhaps you’ve stood in awe before a staircase during your travels, one so breathtaking it left you speechless? The art of staircase craftsmanship has always demanded a blend of creativity and skill at the highest level. The result captivates us through the technical expertise, the staircase type, the staircase style, the chosen materials, the railing and the overall visual impression. A staircase by markiewicz is far more than an everyday building component—it is an architectural and artisanal statement rooted in a clear philosophy.

markiewicz is deeply committed to the rich history of staircase construction. Many of our projects are inspired by historical staircases that represent significant eras of art, style, and technology. Our goal is to make your new staircase a true statement or defining feature of your building, leaving a lasting impression on you and your guests. The media attention and awards we have received for our work underscore the enduring impact our staircases can have.

FROM NATURAL STEPS TO MASTERING ELEVATION: THE ORIGIN OF STAIRCASE DESIGN

The earliest staircases were born out of necessity—to make navigating challenging and uneven terrain as easy and comfortable as possible. Earth's natural landscapes, with their hills, valleys, cliffs, gentle water channels, slopes, and plains, provided early humans with staircase-like formations to explore their environment. Over time, paths that were regularly used to climb inclines became worn down, creating natural steps that served as rudimentary staircases.

Some of the world’s oldest staircase constructions can still be admired today, showcasing their remarkable ingenuity. Often, these early staircases led to high points, such as mountain peaks, symbolizing humanity’s desire to reach closer to the heavens or the divine. Others were designed to descend deep into the earth, fulfilling practical needs such as mining. These early structures highlight the enduring human drive to overcome obstacles and connect with the world around them.

Fig. 4: The Djoser Step Pyramid in Egypt, the world's oldest pyramid (circa 2650 BC), stands at a height of 62.5 meters. It is one of the few pyramids with a base that is not square.

Fig. 5: Starting in 1387, the Calà del Sasso ("Descent from Sasso") is the world's longest publicly accessible outdoor staircase, with 4,444 steps spanning approximately 7 kilometers. It covers an elevation change of about 750 meters, connecting the Asiago Plateau to the town of Valstagna in Italy.

Fig. 6: Bronze Age staircase from the salt mine in Hallstatt, Austria, dated through dendrochronology to the 14th century BC.

THE HISTORIC TRINITY: GEOMETRY, DESIGN, AND AESTHETICS

Temples and pyramids in ancient Greece, pre-Columbian America, and ancient Egypt were often characterized by prominent steps. It seems that the staircase itself was regarded as such a powerful aesthetic element that the master architects of the time embraced its form with artistic enthusiasm, extending beyond its basic functional role as a stepped structure. The grandeur of these constructions and the craftsmanship behind them continue to command our deepest respect even today. For many, visiting one of these millennia-old structures is a once-in-a-lifetime experience that fulfills a long-held dream.

STAIRCASES IN HARMONY WITH NATURE

In the first millennium BC, the Etruscans in Italy carved staircases into the earth to lead to their temples and burial sites (Fig. 7). Nearly 2,000 years later, the majestic stepped terraces of Machu Picchu, built in the 15th century in Peru, became a timeless monument (Fig. 8). At the beginning of the 18th century, the Cascade in the garden of Chatsworth House, located in Derbyshire, England, was constructed (Fig. 9). In our view, it stands as the most beautiful and extraordinary example of landscape-integrated staircase design.

Fig. 7: Etruscan staircase carved from the earth in northern Italy (circa 500 BC).

Fig. 8: Massive, stepped terraces on Montaña Machu Picchu in Peru.

Fig. 9: Cascade House with staircase at the Chatsworth House estate in England.

RENAISSANCE: THE DAWN OF ART IN STAIRCASE DESIGN

In the 15th and 16th centuries, during the Renaissance, the focus in staircase construction shifted from utilizing natural forms to emphasizing human craftsmanship and skill. This was particularly evident in projects that were both heavy and substantial yet simultaneously light and refined in appearance. Artists began to express their creativity and individuality through staircase designs, showcasing them as unique works of art. Notable examples include Michelangelo’s staircase in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (1559–1568, Fig. 10) and Leonardo da Vinci’s visionary design for a mechanical staircase. Da Vinci’s double-helix spiral staircase also emerged during this period. Another striking example of a relatively simple yet elegant staircase is found in the Great Cloister of the Convento de Cristo in Tomar, Portugal, completed in 1557 (Fig. 11).

By the Baroque period (approximately 1600–1750), staircases had gained such significance that they were often constructed with the same level of effort and attention as entire buildings. Many staircases were designed either as expansive additions to structures or as “buildings within buildings.” A prime example of this is Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s spiral staircase (1633–1639), created for the Palazzo Barberini in Rome (Fig. 12). The meticulous arrangement of forms and details, as well as the subsequent preservation and restoration of these structures, became key responsibilities for architects of the era.

Fig. 10: Staircase designed by Michelangelo in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Florence).

Fig. 11: The spiral staircase in the Great Cloister of the Convento de Cristo in Tomar is a key architectural element in one of Portugal's most famous historic buildings.

Fig. 12: Bernini's spiral staircase in the Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

IMPRESSIVE STAIRCASE DESIGNS OF THE 19TH CENTURY

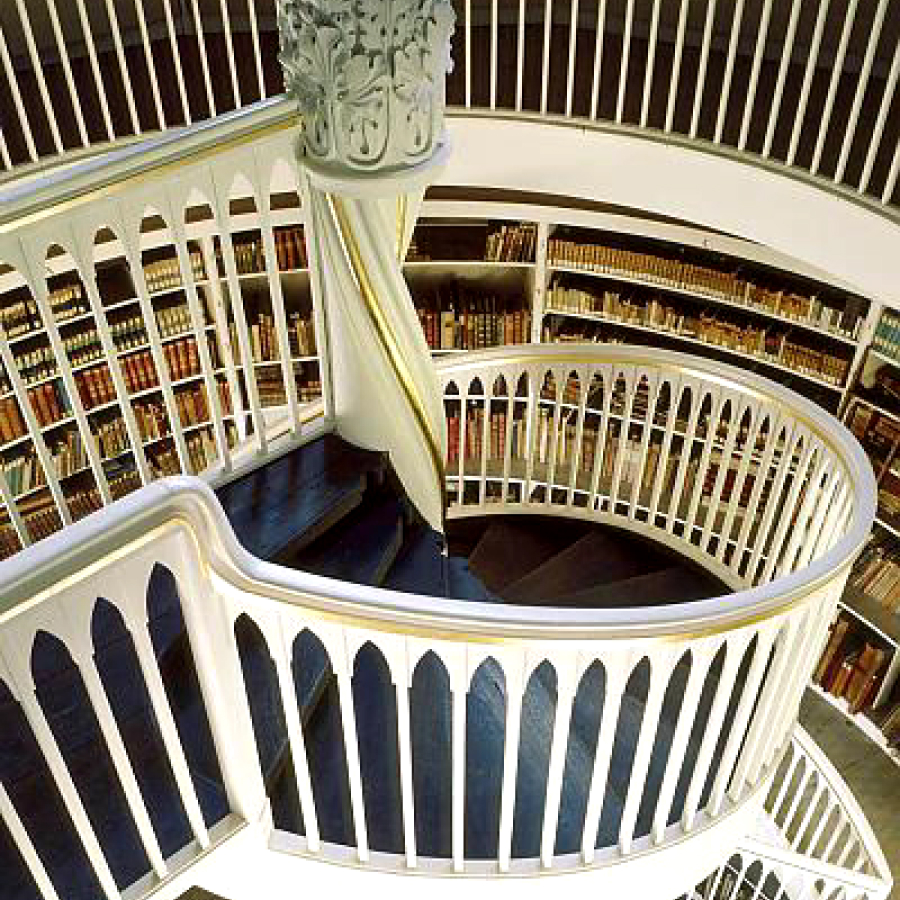

In the early 19th century, an extension (1821–1825) to the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar was constructed, inspired by a suggestion from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. This addition featured a stunning spiral staircase with a spindle carved from a single oak tree (Fig. 13). The craftsmanship displayed in this design far exceeded the usual expectations for library architecture, standing as a testament to exceptional skill and artistry.

As the century progressed, a wealth of artistic and monumental staircases adorned homes, opera houses, theaters, town halls, museums, and train stations. One of the most iconic examples is the monumental staircase designed by Charles Garnier for the Opéra National de Paris (1860–1875), which embodies the lavish grandeur of France’s Second Empire (Fig. 14). With its dramatic design, sensual details, and extravagant scale, it rivals the bold extremes of late Baroque architecture.

Art Nouveau master Victor Horta brought a distinctively flowing and harmonious approach to staircase design, showcasing his ability to transform materials into graceful, fluid forms. This talent is beautifully displayed in the staircase of his own house, built between 1898 and 1900 in Brussels (Fig. 15), which remains a striking example of his unique vision and artistry.

Fig. 13: Staircase in the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar.

Fig. 14: Imperial grand staircase in the Opéra National de Paris.

Fig. 15: Unspeakably beautiful: Staircase in Victor Horta's Brussels residence.

STAIRCASE CONSTRUCTION IN THE 20TH CENTURY

Around a decade later, fellow Belgian architect Henry van de Velde designed a free-floating staircase for the art school in Weimar, now known as the Bauhaus University. This modernist staircase is a prime example of outstanding aesthetics and exceptional craftsmanship (Fig. 16). Van de Velde deliberately chose to redefine construction principles and tone down the artistic excesses of Art Nouveau.

Artistically ahead of his time was the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier, born Charles Édouard Jeanneret-Gris. His Villa Savoye, located in Poissy northwest of Paris, features an elegantly curved interior staircase that is virtually unmatched in beauty (Fig. 17). Built between 1928 and 1931, the villa is rightfully regarded by experts as an architectural icon of modernism. The building adheres to the "Five Points of a New Architecture," which Le Corbusier developed in 1923 together with his cousin and collaborator Pierre Jeanneret.

The enthusiasm for new materials and techniques that swept through the 1930s is evident in the architectural design of Auguste Perret for the Economic and Social Council in Paris (1937–1946). The double staircase within the building was executed with both technical and artistic excellence (Fig. 18). In the preceding decades, there had been increasing efforts to advance the use of concrete, and Perret skillfully applied this material in his elegant design and meticulous craftsmanship. His modest yet refined approach resulted in the understated grandeur that makes this staircase truly remarkable.

Fig. 16: Henry van de Velde's staircase in Weimar's Bauhaus University (1904–1911).

Fig. 17: Curved interior staircase in the Villa Savoye (Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret).

Fig. 18: Double staircase by Auguste Perret for the Economic and Social Council in Paris.

A special fascination emanates from the central staircase designed by American architect Louis Isadore Kahn for the National Parliament Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Fig. 19). Due to interruptions, including those caused by civil war, construction spanned from 1961 to 1982. Tragically, Kahn, who passed away in 1974, was unable to witness the inauguration of his project. The interplay of angular and circular geometric forms captivates visitors, often leaving them pausing in awe as they ascend the staircase. Additionally, the striking contrast of light and shadow adds to the allure of this unique design.

One of the most iconic staircases of the post-war era was created by Oscar Niemeyer for the Palácio do Itamaraty, the headquarters of Brazil's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1960–1970, Fig. 20). Lacking both railings and side walls, the staircase likely violates all safety regulations. Yet, from a technical and architectural perspective, it is undeniably remarkable. Many visitors are left pondering: is this truly a staircase, a sculpture, or perhaps a one-of-a-kind testament to Niemeyer’s unparalleled architectural vision?

No discussion of 20th-century staircase design would be complete without mentioning the unforgettable Italian architect Carlo Scarpa. His staircase for the Brion Cemetery (1970–1972) in San Vito, Italy, is a testament to his ability to achieve monumental results with a limited material palette (Fig. 21). Like Kahn’s staircase in Dhaka, Scarpa's design masterfully employs light and shadow to enhance the extraordinary impact of this architectural masterpiece.

Fig. 19: Geometric forms and captivating light plays in the Bangladesh Parliament Building.

Fig. 20: Oscar Niemeyer's staircase silhouette in the Palácio do Itamaraty in Brasília.

Fig. 21: Carlo Scarpa's staircase at the Brion Cemetery in San Vito, Italy.

MODERN STAIRCASE DESIGN: WHERE TRADITION MEETS DIGITAL INNOVATION

In the past, the construction of impressive staircases was reserved exclusively for the wealthiest and most powerful, often secular or ecclesiastical dignitaries. The historical examples presented here showcase a wide range of methods, ideas, and executions, serving as testaments to the interplay of architectural styles and philosophies.

Today, modern materials have made it possible for anyone to own a unique staircase design. This is largely due to the versatility of staircase construction, which can now be integrated into a broader variety of building types. A closer look at contemporary staircase design reveals how tradition and modernity can be seamlessly combined, particularly in the art of staircase construction.

With globalization taking hold in the second half of the 20th century, the digital revolution, and the rapid advancements in technology and science, nearly all design challenges now seem surmountable. Additionally, the architectural and artistic tolerance of our era appears almost limitless.

The advent of industrial design also left its mark on staircase construction. Prefabricated houses and staircases have become part of mass production. We’ve even heard that staircases can now be made using 3D printing. However, at markiewicz, there is no place for such methods. We see our craft as both traditional and hands-on in the truest sense of the word. At the same time, we stay modern and ensure that we are always up to date with the latest technology and safety standards. This commitment is reflected in our in-house manufactory, where true masters of the craft create extraordinary designs.